New antisemitism

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

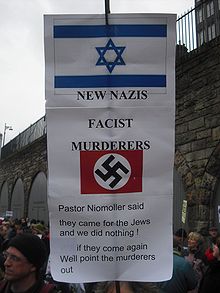

New antisemitism is the concept that a new form of antisemitism developed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, typically manifesting itself as anti-Zionism.[1]: 296–297 The concept is included in some definitions of antisemitism, such as the working definition of antisemitism and the 3D test of antisemitism. The concept dates to the early 1970s.[2]

Proponents of the concept generally posit that in the late 20th and early 21st centuries much of what is purported to be criticism of Israel is in fact tantamount to demonization, and that together with evidence of a resurgence of antisemitic attacks on Jews,[3] desecration of Jewish symbols and Judaism,[3] Holocaust denial,[3] and an increased acceptance of antisemitic beliefs in public discourse and online hate speech,[3] such demonization represents an evolution in the appearance of antisemitic beliefs.[4] Proponents argue that anti-Zionism and demonization of Israel, or double standards applied to its conduct (some also include anti-Americanism, anti-globalization, and Third-Worldism) may be linked to antisemitism, or constitute disguised antisemitism, particularly when emanating simultaneously from the far-left, Islamism, and the far-right.[1]: 296–297 [5][6]

Critics of the concept argue that it is used in practice to weaponize antisemitism in order to silence political debate and freedom of speech regarding the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict, by conflating political anti-Zionism and criticism of the Israeli government with racism, condoning violence against Jews or likening the Israeli government's actions to the Holocaust. Such arguments have in turn been criticized as antisemitic and rhetorically irrelevant to the contested reality of new antisemitism.[7][8] Further critical arguments include that the concept defines legitimate criticism of Israel too narrowly and demonization too broadly, and that it trivializes the meaning of antisemitism.[9][10][11]

History of the concept

1960s: origins

French philosopher Pierre-André Taguieff argues that the first wave of "la nouvelle judéophobie" emerged in the Arab-Muslim world and the Soviet sphere following the 1967 Six-Day War. He cites papers by Jacques Givet (1968) and historian Léon Poliakov (1969) discussing the idea of a new antisemitism rooted in anti-Zionism.[12] He argues that anti-Jewish themes centered on the demonical figures of Israel and what he calls "fantasy-world Zionism": that Jews plot together, seek to conquer the world, and are imperialistic and bloodthirsty, which gave rise to the reactivation of stories about ritual murder and the poisoning of food and water supplies.[13]

1970s: early debates

Writing in the American Jewish Congress' Congress Bi-Weekly in 1973, the Foreign Minister of Israel Abba Eban identified anti-Zionism as "the new anti-Semitism", saying:[14]

[R]ecently we have witnessed the rise of the new left which identifies Israel with the establishment, with acquisition, with smug satisfaction, with, in fact, all the basic enemies ... Let there be no mistake: the new left is the author and the progenitor of the new anti-Semitism. One of the chief tasks of any dialogue with the Gentile world is to prove that the distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism is not a distinction at all. Anti-Zionism is merely the new anti-Semitism. The old classic anti-Semitism declared that equal rights belong to all individuals within the society, except the Jews. The new anti-Semitism says that the right to establish and maintain an independent national sovereign state is the prerogative of all nations, so long as they happen not to be Jewish. And when this right is exercised not by the Maldive Islands, not by the state of Gabon, not by Barbados ... but by the oldest and most authentic of all nationhoods, then this is said to be exclusivism, particularism, and a flight of the Jewish people from its universal mission.

In 1974, Arnold Forster and Benjamin Epstein of the Anti-Defamation League published the book The New anti-Semitism. They expressed concern about what they described as new manifestations of antisemitism coming from radical left, radical right, and pro-Arab figures in the U.S.[15] Forster and Epstein argued that it took the form of indifference to the fears of the Jewish people, apathy in dealing with anti-Jewish bias, and an inability to understand the importance of Israel to Jewish survival.[16]

Reviewing Forster and Epstein's work in Commentary, Earl Raab, founding director of the Nathan Perlmutter Institute for Jewish Advocacy at Brandeis University, argued that a "new anti-Semitism" was indeed emerging in America, in the form of opposition to the collective rights of the Jewish people, but he criticized Forster and Epstein for conflating it with anti-Israel bias.[17] Allan Brownfeld writes that Forster and Epstein's new definition of antisemitism trivialized the concept by turning it into "a form of political blackmail" and "a weapon with which to silence any criticism of either Israel or U.S. policy in the Middle East,"[18] while Edward S. Shapiro, in A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II, has written that "Forster and Epstein implied that the new anti-Semitism was the inability of Gentiles to love Jews and Israel enough."[19]

1980s–present day: continued debate

Historian Robert Wistrich addressed the issue in a 1984 lecture delivered in the home of Israeli President Chaim Herzog, in which he argued that a "new anti-Semitic anti-Zionism" was emerging, distinguishing features of which were the equation of Zionism with Nazism and the belief that Zionists had actively collaborated with Nazis during World War II. He argued that such claims were prevalent in the Soviet Union, but added that similar rhetoric had been taken up by a part of the radical Left, particularly Trotskyist groups in Western Europe and America.[20]

When asked in 2014 if "anti-Zionism is the new anti-Semitism", Noam Chomsky stated:[21]

Actually, the locus classicus, the best formulation of this, was by an ambassador to the United Nations, Abba Eban, ... He advised the American Jewish community that they had two tasks to perform. One task was to show that criticism of the policy, what he called anti-Zionism – that means actually criticisms of the policy of the state of Israel – were anti-Semitism. That's the first task. Second task, if the criticism was made by Jews, their task was to show that it's neurotic self-hatred, needs psychiatric treatment. Then he gave two examples of the latter category. One was I.F. Stone. The other was me. So, we have to be treated for our psychiatric disorders, and non-Jews have to be condemned for anti-Semitism, if they're critical of the state of Israel. That's understandable why Israeli propaganda would take this position. I don't particularly blame Abba Eban for doing what ambassadors are sometimes supposed to do. But we ought to understand that there is no sensible charge. No sensible charge. There's nothing to respond to. It's not a form of anti-Semitism. It's simply criticism of the criminal actions of a state, period.

Definitions and arguments for and against the concept

A new phenomenon

Irwin Cotler, Professor of Law at McGill University and a scholar of human rights, has identified nine aspects of what he considers to constitute the "new anti-Semitism":[22]

- Genocidal antisemitism: calling for the destruction of Israel and/or the Jewish people.

- Political antisemitism: denial of the Jewish people's right to self-determination, de-legitimization of Israel as a state, attributions to Israel of all the world's evils.

- Ideological antisemitism: "Nazifying" Israel by comparing Zionism and racism.

- Theological antisemitism: convergence of Islamic antisemitism and Christian "replacement" theology, drawing on the classical hatred of Jews.

- Cultural antisemitism: the emergence of anti-Israel attitudes, sentiments, and discourse in "fashionable" salon intellectuals.[vague]

- Economic antisemitism: BDS movements and the extraterritorial application of restrictive covenants against countries trading with Israel.

- Holocaust denial.

- Anti-Jewish racist terrorism.

- International legal discrimination ("Denial to Israel of equality before the law in the international arena").

Cotler defines "classical or traditional anti-Semitism" as "the discrimination against, denial of or assault upon the rights of Jews to live as equal members of whatever host society they inhabit" and "new anti-Semitism" as "discrimination against the right of the Jewish people to live as an equal member of the family of nations – the denial of and assault upon the Jewish people's right even to live – with Israel as the "collective Jew among the nations."[23]

Cotler elaborated on this position in a June 2011 interview for Israeli television. He re-iterated his view that the world is "witnessing a new and escalating ... and even lethal anti-Semitism" focused on hatred of Israel, but cautioned that this type of antisemitism should not be defined in a way that precludes "free speech" and "rigorous debate" about Israel's activities. Cotler said that it is "too simplistic to say that anti-Zionism, per se, is anti-Semitic" and argued that labelling Israel as an apartheid state, while in his view "distasteful", is "still within the boundaries of argument" and not inherently antisemitic. He continued: "It's [when] you say, because it's an apartheid state, [that] it has to be dismantled – then [you've] crossed the line into a racist argument, or an anti-Jewish argument."[24]

Jack Fischel, former chair of history at Millersville University of Pennsylvania, writes that new antisemitism is a new phenomenon stemming from a coalition of "leftists, vociferously opposed to the policies of Israel, and right-wing antisemites, committed to the destruction of Israel, [who] were joined by millions of Muslims, including Arabs, who immigrated to Europe... and who brought with them their hatred of Israel in particular and of Jews in general." It is this new political alignment, he argues, that makes new antisemitism unique.[25] Mark Strauss of Foreign Policy links new antisemitism to anti-globalism, describing it as "the medieval image of the "Christ-killing" Jew resurrected on the editorial pages of cosmopolitan European newspapers."[26]

Rajesh Krishnamachari, researcher with the South Asia Analysis Group, analyzed antisemitism in Iran, Turkey, Palestine, Pakistan, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia and posited that the recent surge in antisemitism across the Muslim world should be attributed to political expediency of the local elite in these countries rather than to any theological imperative.[27]

It is the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement refusing to put the Star of David on their ambulances. ... It is neo-Nazis donning checkered Palestinian kaffiyehs and Palestinians lining up to buy copies of Mein Kampf. —Mark Strauss[26]

The French philosopher Pierre-André Taguieff argues that antisemitism based on racism and nationalism has been replaced by a new form based on anti-racism and anti-nationalism. He identifies some of its main features as the identification of Zionism with racism; the use of material related to Holocaust denial (such as doubts about the number of victims and allegations that there is a "Holocaust industry"); a discourse borrowed from third worldism, anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, anti-Americanism and anti-globalization; and the dissemination of what he calls the "myth" of the "intrinsically good Palestinian – the innocent victim par excellence."[28]

In early 2009, 125 parliamentarians from various countries gathered in London for the founding conference of a group called the "Interparliamentary Coalition for Combating Anti-Semitism" (ICCA). They suggest that while classical antisemitism "overlaps" modern antisemitism, it is a different phenomenon and a more dangerous one for Jews.[23]

A new phenomenon, but not antisemitism

Brian Klug, senior research fellow in philosophy at St Benet's Hall, Oxford – who gave expert testimony in February 2006 to a British parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism in the UK, and in November 2004 to the Hearing on Anti-Semitism at the German Bundestag – argues against the idea that there is a "single, unified phenomenon" that could be called "new" antisemitism. He accepts that there is reason for the Jewish community to be concerned, but argues that any increase in antisemitic incidents is attributable to classical antisemitism. Proponents of the new antisemitism concept, he writes, see an organizing principle that allows them to formulate a new concept, but it is only in terms of this concept that many of the examples cited in evidence of it count as examples in the first place.[30] That is, the creation of the concept may be based on a circular argument or tautology. He argues that it is an unhelpful concept, because it devalues the term "antisemitism," leading to widespread cynicism about the use of it. People of goodwill who support the Palestinians resent being falsely accused of antisemitism.[29]

Klug defines classical antisemitism as "an ingrained European fantasy about Jews as Jews," arguing that whether Jews are seen as a race, religion, or ethnicity, and whether antisemitism comes from the right or the left, the antisemite's image of the Jew is always as "a people set apart, not merely by their customs but by their collective character. They are arrogant, secretive, cunning, always looking to turn a profit. Loyal only to their own, wherever they go they form a state within a state, preying upon the societies in whose midst they dwell. Mysteriously powerful, their hidden hand controls the banks and the media. They will even drag governments into war if this suits their purposes. Such is the figure of 'the Jew,' transmitted from generation to generation."[31]

[W]hen anti-Semitism is everywhere, it is nowhere. And when every anti-Zionist is an anti-Semite, we no longer know how to recognize the real thing—the concept of anti-Semitism loses its significance. —Brian Klug[30]

He argues that although it is true that the new antisemitism incorporates the idea that antisemitism is hostility to Jews as Jews, the source of the hostility has changed; therefore, to continue using the same expression for it – antisemitism – causes confusion. Today's hostility to Jews as Jews is based on the Arab–Israeli conflict, not on ancient European fantasies. Israel proclaims itself as the state of the Jewish people, and many Jews align themselves with Israel for that very reason. It is out of this alignment that the hostility to Jews as Jews arises, rather than hostility to Israelis or to Zionists. Klug agrees that it is a prejudice, because it is a generalization about individuals; nevertheless, he argues, it is "not rooted in the ideology of 'the Jew'," and is therefore a different phenomenon from antisemitism.[29]

Norman Finkelstein argues that there has been no significant rise in antisemitism: "What does the evidence show? There has been good investigation done, serious investigation. All the evidence shows there's no evidence at all for a rise of a new anti-Semitism, whether in Europe or in North America. The evidence is zero. And, in fact, there's a new book put out by an Israel stalwart. His name is Walter Laqueur, a very prominent scholar. It's called The Changing Face of Anti-Semitism. It just came out, 2006, from Oxford University Press. He looks at the evidence, and he says no. There's some in Europe among the Muslim community, there's some anti-Semitism, but the notion that in the heart of European society or North American society there's anti-Semitism is preposterous. And in fact – or no, a significant rise in anti-Semitism is preposterous."[32]

Criticism of Israel is not always antisemitism

The 3D Test of Antisemitism is a set of criteria put forth by Natan Sharansky to distinguish legitimate criticism of Israel from antisemitism. The three Ds stand for Delegitimization of Israel, Demonization of Israel, and subjecting Israel to Double standards, each of which, according to the test, indicates antisemitism.[33][34] The test is intended to draw the line between legitimate criticism towards the State of Israel, its actions and policies, and non-legitimate criticism that becomes antisemitic.[35]

Earl Raab writes that "[t]here is a new surge of antisemitism in the world, and much prejudice against Israel is driven by such antisemitism," but argues that charges of antisemitism based on anti-Israel opinions generally lack credibility. He writes that "a grave educational misdirection is imbedded in formulations suggesting that if we somehow get rid of antisemitism, we will get rid of anti-Israelism. This reduces the problems of prejudice against Israel to cartoon proportions." Raab describes prejudice against Israel as a "serious breach of morality and good sense," and argues that it is often a bridge to antisemitism, but distinguishes it from antisemitism as such.[36]

Steven Zipperstein, professor of Jewish Culture and History at Stanford University, argues that a belief in the State of Israel's responsibility for the Arab-Israeli conflict is considered "part of what a reasonably informed, progressive, decent person thinks." He argues that Jews have a tendency to see the State of Israel as a victim because they were very recently themselves "the quintessential victims".[37]

Accusations of misuse of the term to stifle criticism of Israel

Norman Finkelstein argues that organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League have brought forward charges of new antisemitism at various intervals since the 1970s, "not to fight antisemitism but rather to exploit the historical suffering of Jews in order to immunize Israel against criticism".[38] He writes that most evidence purporting to show a new antisemitism has been taken from organizations that are linked in some way to Israel, or that have "a material stake in inflating the findings of anti-Semitism," and that some antisemitic incidents reported in recent years either did not occur or were misidentified.[39] As an example of the misuse of the term "antisemitism," he cites the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia's 2003 report, which included displays of the Palestinian flag, support for the PLO, and the comparisons between Israel and apartheid-era South Africa in its list of antisemitic activities and beliefs.[40]

He writes that what is called the new antisemitism consists of three components: (i) "exaggeration and fabrication"; (ii) "mislabeling legitimate criticism of Israeli policy"; and (iii) "the unjustified yet predictable spillover from criticism of Israel to Jews generally."[42] He argues that Israel's apologists have denied a causal relationship between Israeli policies and hostility toward Jews, since "if Israeli policies, and widespread Jewish support for them, evoke hostility toward Jews, it means that Israel and its Jewish supporters might themselves be causing anti-Semitism; and it might be doing so because Israel and its Jewish supporters are in the wrong".[43]

Tariq Ali, a British-Pakistani historian and political activist, argues that the concept of new antisemitism amounts to an attempt to subvert the language in the interests of the State of Israel. He writes that the campaign against "the supposed new 'anti-semitism'" in modern Europe is a "cynical ploy on the part of the Israeli Government to seal off the Zionist state from any criticism of its regular and consistent brutality against the Palestinians.... Criticism of Israel can not and should not be equated with anti-semitism." He argues that most pro-Palestinian, anti-Zionist groups that emerged after the Six-Day War were careful to observe the distinction between anti-Zionism and antisemitism.[44][45][undue weight? – discuss]

A third wave

Historian Bernard Lewis argues that the new antisemitism represents the third, or ideological, wave of antisemitism, the first two waves being religious and racial antisemitism.[46]

Lewis defines antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of cosmic evil. He writes that what he calls the first wave of antisemitism arose with the advent of Christianity because of the Jews' rejection of Jesus as Messiah. The second wave, racial antisemitism, emerged in Spain when large numbers of Jews were forcibly converted, and doubts about the sincerity of the converts led to ideas about the importance of "la limpieza de sangre", purity of blood.[46]

He associates the third wave with the Arabs and writes that it arose only in part because of the establishment of the State of Israel. Until the 19th century, Muslims had regarded Jews with what Lewis calls "amused, tolerant superiority – they were seen as physically weak, cowardly and unmilitary – and although Jews living in Muslim countries were not treated as equals, they were shown a certain amount of respect. The Western form of antisemitism – what Lewis calls "the cosmic, satanic version of Jew hatred – arrived in the Middle East in several stages, beginning with Christian missionaries in the 19th century and continued to grow slowly into the 20th century up to the establishment of the Third Reich. He writes that it increased because of the humiliation of the Israeli military victories of 1948 and 1967.[46]

Into this mix entered the United Nations. Lewis argues that the international public response and the United Nations' handling of the 1948 refugee situation convinced the Arab world that discrimination against Jews was acceptable. When the ancient Jewish community in East Jerusalem was evicted and its monuments desecrated or destroyed, they were offered no help. Similarly, when Jewish refugees fled or were driven out of Arab countries, no help was offered, but elaborate arrangements were made for Arabs who fled or were driven out of the area that became Israel. All the Arab governments involved in the conflict announced that they would not admit Israelis of any religion into their territories, and that they would not give visas to Jews, no matter which country they were citizens of. Lewis argues that the failure of the United Nations to protest sent a clear message to the Arab world.[46]

He writes that this third wave of antisemitism has in common with the first wave that Jews are able to be part of it. With religious antisemitism, Jews were able to distance themselves from Judaism, and Lewis writes that some even reached high rank within the church and the Inquisition. With racial antisemitism, this was not possible, but with the new, ideological, antisemitism, Jews are once again able to join the critics. The new antisemitism also allows non-Jews, he argues, to criticize or attack Jews without feeling overshadowed by the crimes of the Nazis.[46]

Antisemitism, but not a new phenomenon

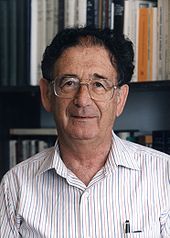

Yehuda Bauer, professor of Holocaust studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, considers the concept "new antisemitism" false, describing the phenomenon as old, latent antisemitism that recurs when triggered. In his view, the current trigger is the Israeli situation, and if a compromise were achieved there antisemitism would decline but not disappear.[47]

Dina Porat, professor at Tel Aviv University says that, while in principle there is no new antisemitism, we can speak of antisemitism in a new envelope. Otherwise Porat speaks of a new and violent form of antisemitism in Western Europe starting after the Second Intifada.[47]

Howard Jacobson, a British novelist and journalist, calls this phenomenon "Jew-hating pure and simple, the Jew-hating which many of us have always suspected was the only explanation for the disgust that contorts and disfigures faces when the mere word Israel crops up in conversation."[48]

An inappropriate redefinition

Antony Lerman, writing in the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz in September 2008, argues that the concept of a "new antisemitism" has brought about "a revolutionary change in the discourse about anti-Semitism". He writes that most contemporary discussions concerning antisemitism have become focused on issues concerning Israel and Zionism, and that the equation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism has become for many a "new orthodoxy". He adds that this redefinition has often resulted in "Jews attacking other Jews for their alleged anti-Semitic anti-Zionism". While Lerman accepts that exposing alleged Jewish antisemitism is "legitimate in principle", he adds that the growing literature in this field "exceeds all reason"; the attacks are often vitriolic, and encompass views that are not inherently anti-Zionist.

Lerman argues that this redefinition has had unfortunate repercussions. He writes that serious scholarly research into contemporary antisemitism has become "virtually non-existent", and that the subject is now most frequently studied and analyzed by "people lacking any serious expertise in the subject, whose principal aim is to excoriate Jewish critics of Israel and to promote the "anti-Zionism = anti-Semitism" equation. Lerman concludes that this redefinition has ultimately served to stifle legitimate discussion, and that it cannot create a basis on which to fight antisemitism.[49]

Peter Beaumont, writing in The Observer, agrees that proponents of the concept of "new antisemitism" have attempted to co-opt anti-Jewish sentiment and attacks by some European Muslims as a way to silence opposition to the policies of the Israeli government. "[C]riticise Israel," he writes, "and you are an anti-Semite just as surely as if you were throwing paint at a synagogue in Paris."[50]

Antisemitic anti-Zionism

Scholars including Werner Bergmann, Simon Schama, Alan Johnson, David Hirsh and Anthony Julius have described a distinctively 21st century form of antisemitic anti-Zionism characterized by left-wing hostility to Jews.[51][52][53][54][55] According to historian Geoffrey Alderman, opposition to Zionism (being against a Jewish state) can be legitimately described as racist in essence.[56][57]

In 2024, over 1000 entertainers, authors and artists signed an open letter, released by the non-profit Creative Community for Peace (CCFP), opposing boycotts of Israeli and Jewish authors and literary institutions. The letter decried efforts to "demonize and ostracize Jewish authors across the globe".[58]

International perspectives

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2012) |

Europe

The European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC) (superseded in 2007 by the Fundamental Rights Agency) noted an upswing in antisemitic incidents in France, Germany, Austria, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and The Netherlands between July 2003 and December 2004.[59] In September 2004, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, a part of the Council of Europe, called on its member nations to ensure that anti-racist criminal law covers antisemitism, and in 2005, the EUMC offered a discussion paper on a working definition of antisemitism in an attempt to enable a standard definition to be used for data collection:[60] It defined antisemitism as "a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred towards Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed towards Jews and non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, towards Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." The paper's “Examples of the ways in which anti-Semitism manifests itself with regard to the state of Israel taking into account the overall context could include":

- Denying the Jewish people the right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor;

- Applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation;

- Using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (e.g. claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis;

- Drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.

- Holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel.[61][62]

The EUMC added that criticism of Israel cannot be regarded as antisemitism so long as it is "similar to that leveled against any other country."[61]

The discussion paper was never adopted by the EU as a working definition, although it was posted on the EUMC website until 2013 when it was removed during a clear-out of non-official documents.[63][64]

France

In France, Interior Minister Dominique de Villepin commissioned a report on racism and antisemitism from Jean-Christophe Rufin, president of Action Against Hunger and former vice-president of Médecins Sans Frontières, in which Rufin challenges the perception that the new antisemitism in France comes exclusively from North African immigrant communities and the far right.[65][66]

Reporting in October 2004, Rufin writes that "[t]he new anti-Semitism appears more heterogeneous," and identifies what he calls a new and "subtle" form of antisemitism in "radical anti-Zionism" as expressed by far-left and anti-globalization groups, in which criticism of Jews and Israel is used as a pretext to "legitimize the armed Palestinian conflict."[67][68]

United Kingdom

In June 2011, Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, Jonathan Sacks (Lord Sacks), said that the basis for the new antisemitism was the 2001 Durban Conference. Rabbi Sacks also said that the new antisemitism "unites radical Islamists with human-rights NGOs – the right wing and the left wing – against a common enemy, the State of Israel."[69]

In September 2006, the All-Party Parliamentary Group against Anti-Semitism of the British parliament published the Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Antisemitism, the result of an investigation into whether the belief that the "prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond" that antisemitism had "receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." was correct. It concluded that "the evidence we received indicates that there has been a reversal of this progress since the year 2000". In defining antisemitism, the Group wrote that it took into account the view of racism expressed by the MacPherson report, which was published after the murder of Stephen Lawrence, that, for the purpose of investigating and recording complaints of crime by the police, an act must be recorded by the police as racist if it is defined as such by its victim. It formed the view that, broadly, "any remark, insult or act the purpose or effect of which is to violate a Jewish person's dignity or create an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for him is antisemitic" and concluded that, given that, "it is the Jewish community itself that is best qualified to determine what does and does not constitute antisemitism."[70]

The report states that some left-wing activists and Muslim extremists are using criticism of Israel as a "pretext" for antisemitism,[71] and that the "most worrying discovery" is that antisemitism appears to be entering the mainstream.[72] It argues that anti-Zionism may become antisemitic when it adopts a view of Zionism as a "global force of unlimited power and malevolence throughout history," a definition that "bears no relation to the understanding that most Jews have of the concept: that is, a movement of Jewish national liberation ..." Having re-defined Zionism, the report states, traditional antisemitic motifs of Jewish "conspiratorial power, manipulation and subversion" are often transferred from Jews onto Zionism. The report notes that this is "at the core of the 'New Antisemitism', on which so much has been written," adding that many of those who gave evidence called anti-Zionism "the lingua franca of antisemitic movements."[73]

Israel

In November 2001 according to the Israeli Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, in response to an Abu-Dhabi television broadcast depicting Ariel Sharon drinking the blood of Palestinian children, the Israeli government set up the "Coordinating Forum for Countering Antisemitism", headed by Deputy Foreign Minister Rabbi Michael Melchior. According to Melchior, "in each and every generation antisemitism tries to hide its ugly face behind various disguises – and hatred of the State of Israel is its current disguise." He added that, "hate against Israel has crossed the red line, having gone from criticism to unbridled antisemitic venom, which is a precise translation of classical antisemitism whose past results are all too familiar to the entire world."[74]

United Nations

A number of commentators argue that the United Nations has condoned antisemitism. Lawrence Summers, then-president of Harvard University, wrote that the UN's World Conference on Racism failed to condemn human rights abuses in China, Rwanda, or anywhere in the Arab world, while raising Israel's alleged ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.[75]

David Matas, senior counsel to B'nai B'rith Canada, has written that the UN is a forum for antisemitism, citing the example of the Palestinian representative to the UN Human Rights Commission who claimed in 1997 that Israeli doctors had injected Palestinian children with the AIDS virus.[76] Congressman Steve Chabot told the U.S. House of Representatives in 2005 that the commission took "several months to correct in its record a statement by the Syrian ambassador that Jews allegedly had killed non-Jewish children to make unleavened bread for Passover.[77]

Anne Bayefsky, a Canadian legal scholar who addressed the UN about its treatment of Israel, argues that the UN hijacks the language of human rights to discriminate and demonize Jews. She writes that over one quarter of the resolutions condemning a state's human rights violations have been directed at Israel. "But there has never been a single resolution about the decades-long repression of the civil and political rights of 1.3 billion people in China, or the million female migrant workers in Saudi Arabia kept as virtual slaves, or the virulent racism which has brought 600,000 people to the brink of starvation in Zimbabwe."[78]

In a 2008 report on antisemitism from the United States Department of State to the US Congress,[79]

Motives for criticizing Israel in the UN may stem from legitimate concerns over policy or from illegitimate prejudices. ... However, regardless of the intent, disproportionate criticism of Israel as barbaric and unprincipled, and corresponding discriminatory measures adopted in the UN against Israel, have the effect of causing audiences to associate negative attributes with Jews in general, thus fueling anti-Semitism.

United States

In September 2006, Yale University announced that it had established the Yale Initiative for the Interdisciplinary Study of Anti-Semitism,[80] the first university-based institute in North America dedicated to the study of antisemitism. Charles Small, head of the institute, said in a press release that antisemitism has "reemerged internationally in a manner that many leading scholars and policy makers take seriously ... Increasingly, Jewish communities around the world feel under threat. It's almost like going back into the lab. I think we need to understand the current manifestation of this disease."[81] YIISA has presented several seminars and working papers on the topic, for instance "The Academic and Public Debate Over the Meaning of the 'New Antisemitism'".[82]

In July 2006, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights issued a Campus Antisemitism report that declared that "Anti-Semitic bigotry is no less morally deplorable when camouflaged as anti-Israelism or anti-Zionism."[83] At the time, the commission also announced that antisemitism is a "serious problem" on many campuses throughout the United States.[84]

The U.S. State Department's 2004 Report on Global Anti-Semitism identified four sources of rising antisemitism, particularly in Europe:

- "Traditional anti-Jewish prejudice... This includes ultra-nationalists and others who assert that the Jewish community controls governments, the media, international business, and the financial world."

- "Strong anti-Israel sentiment that crosses the line between objective criticism of Israeli policies and anti-Semitism."

- "Anti-Jewish sentiment expressed by some in Europe's growing Muslim population, based on longstanding antipathy toward both Israel and Jews, as well as Muslim opposition to developments in Israel and the occupied territories, and more recently in Iraq."

- "Criticism of both the United States and globalization that spills over to Israel, and to Jews in general who are identified with both."[59]

Anti-globalization movement

The anti-globalization movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s was accused by writers and researchers such as Walter Laqueur, Paul Berman, and Mark Strauss of displaying elements of new antisemitism. Critics of the Laqueur–Berman–Strauss view argue that the allegation is either unfounded or exaggerated, intended to discredit legitimate criticism of globalization and of free trade economic policies.[citation needed]

Mark Strauss's allegations

Mark Strauss of Foreign Policy argues that globalization has stirred anxieties about "outside forces", and that with "familiar anxieties come familiar scapegoats."[85] He writes that what he calls the "backlash against globalization" has united a variety of political elements, from the left to the far-right, via a common cause, and that in so doing it has "foster[ed] a common enemy." He quotes the French Jewish leader Roger Cukierman who identifies the anti-globalization movement as "an anti-Semitic brown-green-red alliance", which includes ultra-nationalists, Islamists, and communists.[85]

Strauss cites Jörg Haider of the far-right Freedom Party of Austria and Jean-Marie Le Pen of France's National Front as examples of the far right exploiting their electorate's concerns about globalization. The fringe Fascism and Freedom Movement in Italy identifies globalization as an "instrument in the hands of international Zionism" according to Strauss, while in Eastern Europe ultranationalists and communists have united against foreign investors and multinationals, identifying Jews as a common enemy.[85]

Matthew F. Hale, an American white nationalist of the World Church of the Creator, stated of the 1999 protests in Seattle that they were "incredibly successful from the point of view of the rioters as well as our Church. They helped shut down talks of the Jew World Order WTO and helped make a mockery of the Jewish Occupational Government around the world. Bravo."[85] Strauss also cites the National Alliance, a neo-Nazi party which set up a website called the Anti-Globalism Action Network in order to "broaden ... the anti-globalism movement to include divergent and marginalized voices."[85]

Strauss writes that, as a result of far-right involvement, a "bizarre ideological turf war has broken out", whereby anti-globalization activists are fighting a "two-front battle," one against the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund, and World Bank, the other against the extremists who turn up at their rallies.[85] He points to an anti-globalization march in Porto Alegre, Brazil, at which he says some marchers displayed swastikas and that Jewish peace activists were assaulted. He wrote:

"Held two months prior to the U.S.-led attack on Iraq, this year's conference – an annual grassroots riposte to the well-heeled World Economic Forum in Davos – had the theme, 'Another World is Possible.' But the more appropriate theme might have been 'Yesterday's World is Back.' Marchers among the 20,000 activists from 120 countries carried signs reading 'Nazis, Yankees, and Jews: No More Chosen Peoples!' Some wore T-shirts with the Star of David twisted into Nazi swastikas. Members of a Palestinian organization pilloried Jews as the 'true fundamentalists who control United States capitalism.' Jewish delegates carrying banners declaring 'Two peoples – Two states: Peace in the Middle East' were assaulted.[85]

Strauss argues that the anti-globalization movement is not itself antisemitic but that it "helps enable anti-Semitism by peddling conspiracy theories."[85] Strauss's arguments have been met with strong criticism from many in the anti-globalization movement. Oded Grajew, one of the founders of the World Social Forum, has written that the WSF "is not anti-Semitic, anti-American, or even anti-socially-responsible capitalism". He claims that some fringe parties have attempted to infiltrate the WSF's demonstrations and promote demonstrations of their own, but adds that "[t]he success of the WSF ... is a threat to political extremist groups that resort to violence and hatred". Grajew has also written that, to his knowledge, Strauss's claim of Nazi symbols being displayed at an anti-globalization demonstration in Porto Alegre, Brazil is false.[86]

Response to Strauss

Maude Barlow, national chairperson of the Council of Canadians, argues that Strauss has "inflamed, not enlightened" the debate over globalization by making "no distinction between the far right's critique of globalization and that of the global social justice movement", which is premised on "respect for human rights and cultural diversity". She notes that the Council of Canadians has condemned antisemitism, and that it expelled some individuals who tried to organize a David Icke tour under its auspices.[87] John Cavanagh of the International Policy Centre has also criticized Strauss for using unproven allegations of antisemitism to criticize the entire anti-globalization movement, and for failing to research the movement's core beliefs.[88]

In response to these criticisms, Strauss has written that antisemitic views "might not reflect the core values of the Global Justice Movement or its leading figures, yet they are facts of life in an amorphous, grassroots movement where any number of individuals or organizations express their opinions or seek to set the agenda". He has also reiterated his concern that "anti-capitalist rhetoric provides intellectual fodder for far right groups".[89]

Other views

Walter Laqueur describes this phenomenon:[90]

Although traditional Trotskyite ideology is in no way close to radical Islamic teachings and the shariah, since the radical Islamists also subscribed to anticapitalism, antiglobalism, and anti-Americanism, there seemed to be sufficient common ground for an alliance. Thus, the militants of the far left began to march side by side with the radical Islamists in demonstrations, denouncing American aggression and Israeli crimes. ... And it was only natural that in protest demonstrations militants from the far right would join in, antisemitic banners would be displayed, anti-Jewish literature such as the Protocols would be sold.

Lawrence Summers, then president of Harvard University, also stated that "[s]erious and thoughtful people are advocating and taking actions that are anti-Semitic in their effect if not their intent. For example ... [a]t the same rallies where protesters, many of them university students, condemn the IMF and global capitalism and raise questions about globalization, it is becoming increasingly common to also lash out at Israel. Indeed, at the anti-IMF rallies last spring, chants were heard equating Hitler and Sharon."[91]

A March 2003 report on antisemitism in the European Union by Werner Bergmann and Juliane Wetzel of the Berlin Research Centre on Anti-Semitism identifies anti-globalization rallies as one of the sources of antisemitism on the left.[92]

In the extreme left-wing scene, anti-Semitic remarks were to be found mainly in the context of pro-Palestinian and anti-globalisation rallies and in newspaper articles using anti-Semitic stereotypes in their criticism of Israel. Often this generated a combination of anti-Zionist and anti-American views that formed an important element in the emergence of an anti-Semitic mood in Europe.[51]

Michael Kozak, then U.S. Acting Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, told reporters in 2005 that people within the anti-globalization movement have conflated their legitimate concerns "with this idea that Jews run the world and globalization is the fault of Jews."[93] He said:[93]

I think one of the disturbing things is that you're starting to see this in some – you know, it's not just sort of right-wing ultranationalist skinhead types. It's now you're getting some fairly otherwise respectable intellectuals that are left of center who are anti-globalization who are starting to let this stuff creep into their rhetoric.

And that's disturbing because it starts to – it starts to take what is a legitimate issue for debate, anti-globalization or the war in Iraq or any other issue, and when you start turning that into an excuse for saying therefore we should hate Jews, that's where you cross the line, in my view. It's not that you're not entitled to question all those other issues. Of course, those are fair game. But it's the same as saying, you know, you start hating all Muslims because of some policy you don't like by one Muslim country or something.

Conflation of globalization, Jews and Israel

Robert Wistrich, Professor of European and Jewish History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told Manfred Gerstenfeld that globalization has given rise to an anti-globalist left that is "viscerally anti-American, anti-capitalist, and hostile to world Jewry."[94] He argues that the decade that preceded the current increase in antisemitism was one that saw accelerated globalization of the world economy, a process in which the losers included the Arab and Muslim worlds, and who are now the "major consumers of anti-Jewish poison and conspiracy theories that blame everyone except themselves. Israel is only one piece on this chessboard, but it has assumed such inflated importance because it serves a classic anti-Semitic function of being an 'opium for the masses'."[94] As an example of the alleged conflation of globalization, the U.S. and Israel, Josef Joffe, editor and publisher of Die Zeit and adjunct professor at Stanford University, cited José Bové, a French anti-globalization activist and leader of the Confédération Paysanne.[95] Bové led what Joffe calls a "deconstructionist mob" against McDonald's to protest against its effects on French cuisine, later turning up in Ramallah to denounce Israel and announce his support for Yasser Arafat. "Arafat's cause was Bové's cause ... here was a spokesman for the anti-globalization movement who was conflating globalization with Americanization and extending his loathing of both to Israel."[96] Joffe argues that Kapitalismuskritik is a "mainstay of the antisemitic faith, a charge that has passed smoothly from Jews to America. Like Jews, Americans are money-grubbers who know only the value of money, and the worth of nothing. Like Jews, they seek to reduce all relationships to exchange and money. Like them, Americans are motivated only by profit, and so they respect no tradition."[97]

David Clark, writing in The Guardian, argues against this that "instances of anti-capitalism spilling into 'rich Jew' bigotry are ... well documented" but "stand out precisely because they conflict so sharply with the Left's universalism and its opposition to ethnic discrimination".[98]

In early 2004, Kalle Lasn, author of "Culture Jam" and founder of Adbusters, two influential and widely read anti-globalization texts, generated controversy when he wrote an editorial entitled "Why won't anyone say they are Jewish?".[99] In it he stated "Drawing attention to the Jewishness of the neocons is a tricky game. Anyone who does so can count on automatically being smeared as an anti-Semite. But the point is not that Jews (who make up less than 2 percent of the American population) have a monolithic perspective. Indeed, American Jews overwhelmingly vote Democrat and many of them disagree strongly with Ariel Sharon's policies and Bush's aggression in Iraq. The point is simply that the neocons seem to have a special affinity for Israel that influences their political thinking and consequently American foreign policy in the Middle East."[99] The editorial suggested that Jews represent a disproportionately high percentage of the neo-conservatives who control American foreign policy, and that this may affect policy with respect to Israel.[100] Lasn included a list of influential neo-conservatives, with dots next to the names of those who were Jewish.[99]

Lasn was criticized by a number of anti-globalization activists. Klaus Jahn, professor of the philosophy of history at the University of Toronto condemned Lasn's article stating "Whether listing physicians who perform abortions in anti-abortion tracts, gays and lesbians in office memos, Communists in government and the entertainment industry under McCarthy, Jews in Central Europe under Nazism and so on, such list-making has always produced pernicious consequences."[101]

Meredith Warren, a Montreal anti-globalization activist responded to the article by saying "The U.S. government has only an economic interest in having control over that region. It wants oil and stability – it has nothing to do with Jews or Judaism. Pointing out the various religious stances of those in power totally misses the point of the U.S. government's interest in Israel."[101]

Controversy over alleged antisemitism within the French movement

According to a report by the Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, a major event for the anti-globalization movement in France was the European Social Forum (ESF) in Paris in November 2003. The organizers allegedly included a number of Islamic groups, such as Présence Musulmane, Secours Islamique, and Collectif des Musulmans de France. Tariq Ramadan, the grandson of Hassan al-Banna, the Egyptian founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, also attended meetings. A few weeks earlier, Ramadan had published a controversial article on a website – after Le Monde and Le Figaro refused to publish it – criticizing several French intellectuals, who according to the institute, were either Jewish or "others he mistakenly thought were Jewish," for having "supposedly betrayed their universalist beliefs in favor of unconditional support for Zionism and Israel."[95]

Bernard-Henri Lévy, one of the intellectuals who was criticized, called on the French anti-globalization movement to distance itself from Ramadan. In an interview with Le Monde, Lévy said: "Mr. Ramadan, dear anti-globalizationist friends, is not and cannot be one of yours. ... I call you on you quickly to distance yourselves from this character who, in crediting the idea of an elitist conspiracy under the control of Zionism, is only inflaming people's thoughts and opening the way to the worst."[102]

Le Monde reported that many members of the anti-globalization movement in France agreed that Ramadan's article "has no place on a European Social Forum mailing list."[102]

Other activists defended Ramadan. One activist told the newspaper that "[o]ne of the characteristics of the European Social Forum is the stark rise in immigrant and Muslim organizations. It is an important phenomenon and a positive one in many ways."[102] Another activist, Peter Khalfa, said: "Ramadan's essay is not anti-Semitic. It is dangerous to wave the red flag of anti-Semitism at any moment. However, it is a text marked partly by Ramadan's communitarian thought and which communicates his view of the world to others."[102] One of the leaders of the anti-globalization movement in France, José Bové of the Confédération Paysanne, told Le Monde: "The anti-globalization movement defends universalist points of view which are therefore necessarily secular in their political expression. That there should be people of different cultures and religions is only natural. The whole effort is to escape such determinisms."[102]

Concern within the political left

Naomi Klein, a Jewish Canadian writer and activist in the anti-globalization movement, expressed concern in 2002 at finding antisemitic rhetoric on some activist websites that she had visited: "I couldn't help thinking about all the recent events I've been to where anti-Muslim violence was rightly condemned, but no mention was made of attacks on Jewish synagogues, cemeteries, and community centers."[103] Klein urged activists to confront antisemitism as part of their work for social justice. She also suggested that allegations of antisemitism can be often politically motivated, and that activists should avoid political simplifications that could be perceived as antisemitic:[103]

The [anti-]globalization movement isn't anti-Semitic, it just hasn't fully confronted the implications of diving into the Middle East conflict. Most people on the left are simply choosing sides. In the Middle East, where one side is under occupation and the other has the U.S. military behind it, the choice seems clear. But it is possible to criticize Israel while forcefully condemning the rise of anti-Semitism. And it is equally possible to be pro-Palestinian independence without adopting a simplistic pro-Palestinian/anti-Israel dichotomy, a mirror image of the good versus evil equations so beloved by President George W. Bush.

In October 2004, the New Internationalist magazine published a special issue covering the insertion of antisemitic rhetoric into some progressive debates.[104] Adam Ma'anit wrote:[105]

Take Adbusters magazine's founder Kalle Lasn's recent editorial rant against Jewish neoconservatives. ... The article includes a self-selected 'well-researched list' of 50 of the supposedly most influential 'neocons' with little black dots next to all those who are Jewish. ... If it's not the neocons then it's the all-powerful 'Jewish lobby' which holds governments to ransom all over the world (because Jews control the global economy of course) to do their bidding. Meanwhile, rightwing Judeophobes often talk of a leftist Jewish conspiracy to promote equality and human rights through a new internationalism embodied in the UN in order to control governments and suppress national sovereignty. They call it the 'New World Order' or the 'Jew World Order'. They make similar lists to Lasn's of prominent Jews in the global justice movement (Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, etc.) to argue their case.

The issue observes, however, that "While antisemitism is rife in the Arab World, the Israeli Government often uses it as moral justification for its policies."[106]

Notes

- ^ a b Fastenbauer, Raimund (2020). "Islamic Antisemitism: Jews in the Qur'an, Reflections of European Antisemitism, Political Anti-Zionism: Common Codes and Differences". In Lange, Armin; Mayerhofer, Kerstin; Porat, Dina; Schiffman, Lawrence H. (eds.). An End to Antisemitism! – Volume 2: Confronting Antisemitism from the Perspectives of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 279–300. doi:10.1515/9783110671773-018. ISBN 9783110671773.

- ^ Berkman, Matthew (2022). "The Conflict on Campus". In A. Siniver (ed.). Routledge Companion to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Taylor & Francis. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-429-64861-8. Retrieved 2023-05-21.

Attempts to rearticulate antisemitism to encompass opposition to Israel's "right to exist" or its character as a Jewish state date back to the 1970s, when the Anti-Defamation League first popularized a discourse on "the new antisemitism" (see Forster and Epstein 1974; on the subsequent development of that discourse see Judaken 2008). The identification of anti-Zionism with antisemitism has long been de rigueur in Jewish communal and broader pro-Israel circles, but only in the last two decades have Israel advocacy groups endeavoured to establish it as a principle of United States anti-discrimination law. The earliest step in this direction was taken in 2004, when Kenneth L. Marcus, the Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) under President George W. Bush, issued a game-changing policy guidance letter empowering OCR staff, for the first time, to investigate complaints under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act alleging pervasive antisemitism on college campuses.

- ^ a b c d "USCIRF 2020 Annual Report: "Rising Anti-Semitism in Europe and Elsewhere"" (PDF). Uscirf.gov. Washington, D.C.: United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. April 2020. pp. 87–88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Manfred Gerstenfeld, The Deep Roots of Anti-Semitism in European Society. Jewish Political Studies Review 17:1–2 Spring 2005

- ^ Taguieff, Pierre-André. Rising From the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe. Ivan R. Dee, 2004.

- ^ Cohen, Florette (September 2011). The New Anti-Semitism Israel Model: Empirical Tests. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-243-56139-8.

- ^ Hirsh, David (January 2010). "Accusations of malicious intent in debates about the Palestine-Israel conflict and about antisemitism: The Livingstone Formulation, 'playing the antisemitism card' and contesting the boundaries of antiracist discourse" (PDF). Transversal: 47–77.

- ^ Klaff, Lesley (2016-12-01), Wistrich, Robert S. (ed.), Holocaust inversion in British politics : the case of David Ward, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 185–196, ISBN 978-0-8032-9671-8, retrieved 2024-01-09

- ^ Klug, Brian. The Myth of the New Anti-Semitism. The Nation, posted January 15, 2004 (February 2, 2004 issue), accessed January 9, 2006; and Lerner, Michael. There Is No New Anti-Semitism, posted February 5, 2007, accessed February 6, 2007.

- ^ Steven Beller, 'In Zion’s hall of mirrors: a comment on Neuer Antisemitismus?,' Patterns of Prejudice, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2007 pp.215-238, 223:' The idea that there has been an explosion of antisemitic sentiment in Europe has more to do with American, Israeli and Zionist discomfort with strong European criticism of Israeli policy than it has with actual antisemitism.'

- ^ Scott Ury, 'Strange Bedfellows? Anti-Semitism, Zionism, and the Fate of “the Jews”,' American Historical Review, October 2018, vol. 123, 4 pp. 1151-1171, p.1552: 'One of the biggest problems facing the study of anti-Semitism today: its ongoing, seemingly inescapable connection to public affairs and the extent to which contemporary political concerns, in particular those regarding Zionism and the State of Israel, influence and shape the way that many scholars frame, interpret, and research anti-Semitism.'

- ^ Pierre-André Taguieff cites the following early works on the new antisemitism: Jacques Givet, La Gauche contre Israel? Essai sur le néo-antisémitisme, Paris 1968; idem, "Contre une certain gauche," Les Nouveaux Cahiers, No. 13-14, Spring-Summer 1968, pp. 116–119; Léon Poliakov, De l'antisionisme a l'antisémitisme, Paris 1969; Shmuel Ettinger, "Le caractère de l'antisémitisme contemporain," Dispersion et Unité, No. 14, 1975, pp. 141–157; and Michael Curtis, ed., Antisemitism in the Modern World, Boulder, 1986. All cited in Pierre-André Taguieff. Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe. Ivan R. Dee, 2004, p. 159-160, footnote 1.

- ^ Taguieff, Pierre André. Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe. Ivan R. Dee, 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Congress Bi-weekly, American Jewish Congress, Vol. 40, Issues 2-14, 1973, p. xxv

- ^ Forster, Arnold & Epstein, Benjamin, The New Anti-Semitism. McGraw-Hill 1974, p.165. See for instance chapters entitled "Gerald Smith's Road" (19–48), "The Radical Right" (285–296), "Arabs and Pro-Arabs" (155–174), "The Radical Left" (125–154)

- ^ Forster, Arnold & Epstein, Benjamin, The New Anti-Semitism. McGraw-Hill 1974, p. 324.

- ^ Raab, Earl. "Is there a New Anti-Semitism?", Commentary, May 1974, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Brownfeld, Allan (1987). "Anti-Semitism: Its Changing Meaning". Journal of Palestine Studies. 16 (3). Institute for Palestine Studies: 53–67. doi:10.2307/2536789. ISSN 1533-8614. JSTOR 2536789.

- ^ Edward S. Shapiro. A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II. Johns Hopkins University Press. 1992. ISBN 0-8018-4347-2. Page 47.

- ^ Wistrich, Robert. "Anti-zionism as an Expression of Anti-Semitism in Recent Years" Archived 2017-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, lecture delivered to the Study Circle on World Jewry in the home of the President of Israel, December 10, 1984.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam. "TRANSCRIPT of Amy Goodman interview of Noam Chomsky". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Irwin Cotler cited Dershowitz, Alan. The Case For Israel. John Wiley and Sons, 2003, p. 210-211.

- ^ a b Irwin Cotler, Making the world 'Judenstaatrein'[permanent dead link], The Jerusalem Post, February 22, 2009.

- ^ David Sheen, "Canadian MP Cotler: Calling Israel an apartheid state can be legitimate free speech", Haaretz, 1 July 2011. Accessed 7 July 2011.

- ^ Fischel, Jack R. "The New Anti-Semitism", The Virginia Quarterly Review, Summer 2005, pp. 225–234.

- ^ a b Strauss, Mark (2009-11-02). "Anti-globalism's Jewish Problem". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ Tembarai Krishnamachari, Rajesh. "Localized motivations for antisemitism within the Ummah"[usurped] in South Asia Analysis Group, Paper 5907, April 2015.

- ^ Taguieff, Pierre-André. Rising From the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe. Ivan R. Dee, 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c Klug, Brian. "In search of clarity" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Catalyst, March 17, 2006.

- ^ a b Klug, Brian. The Myth of the New Anti-Semitism Archived 2009-07-01 at the Portuguese Web Archive. The Nation, February 2, 2004, accessed January 9, 2006

- ^ Klug, Brian. Israel, Antisemitism and the left Archived 2006-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Red Pepper, November 24, 2005.

- ^ Goodman, Amy. "Finkelstein on DN! No New Antisemitism" Archived 2006-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, interview with Norman Finkelstein, August 29, 2006.

- ^ "So What's New? Rethinking the 'New Antisemitism' in a Global Age" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-27.

- ^ "Remarks at the 2011 B'nai B'rith International Policy Conference". 2012-12-02. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ Cohen, Florette (September 2011). The New Anti-Semitism Israel Model: Empirical Tests. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-243-56139-8.

- ^ Raab, Earl. "Antisemitism, anti-Israelism, anti-Americanism", Judaism, Fall 2002.

- ^ Zipperstein, Steven. "Historical Reflections of Contemporary Antisemitism" in Derek J. Penslar et al., ed., Contemporary Antisemitism: Canada and the World, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, p. 66–71.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, University of California Press, 2005, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (1 May 2018). Street Fighting Years: An Autobiography of the Sixties. Verso Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-78663-602-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Julius, Anthony (9 February 2012). Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England. Oxford University Press. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-19-960072-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, Bernard. "The New Anti-Semitism" Archived 2011-09-08 at the Wayback Machine, The American Scholar, Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36 The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on March 24, 2004.

- ^ a b Tzvi Fleischer (May 2007). "Hate's Revival". Australia/Israel Review. AIJAC.

- ^ Fulford, Robert (2009-08-15). "When criticizing Israel becomes ritual". nationalpost.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Antony Lerman, "Jews attacking Jews", Ha'aretz, 12 September 2008, accessed 13 September 2008.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter. "The new anti-semitism?", The Observer, February 17, 2002.

- ^ a b Pelinka, Anton; et al. (2009). Handbook of Prejudice. Chapter on Anti-Semitism by Werner Bergmann. Cambria Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-60497-627-4.

- ^ Schama, Simon (19 February 2016). "The left's problem with Jews has a long and miserable history". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Hirsh, David (30 November 2006). "Openly Embraing Prejudice". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Julius, Anthony (2010). Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England. Oxford University Press. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-19-929705-4.

- ^ Johnson, Alan (Fall 2015). "The Left and the Jews: Time for a Rethink". Fathom. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Alderman, Geoffrey (November 8, 2012). "Why anti-Zionists are racists". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Formula Could Combat Campus Racism". Jewish Weekly. June 5, 2005. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Kaloi, Stephanie (2024-10-31). "David Mamet, Diane Warren and Debra Messing Among 1000+ Entertainers and Artists to Oppose Israel Boycotts in Open Letter". TheWrap. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ a b "(U.S.) State Department report on Anti-Semitism: Europe and Eurasia" excerpted from a longer piece, and covering the period of July 1, 2003 – December 15, 2004.

- ^ Whine, Michael. "Progress in the Struggle Against Anti-Semitism in Europe: The Berlin Declaration and the European Union Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia's Working Definition of Anti-Semitism" Archived 2022-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism, Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, February 1, 2006.

- ^ a b tp://eumc.eu.int/eumc/material/pub/AS/AS-WorkingDefinition-draft.pdf "Working definition of antisemitism" Archived 2011-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, EUMC.

- ^ "Working Definition of Antisemitism" (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "SWC to EU Baroness Ashton: "Return Anti-Semitism Definition Document to EU Fundamental Rights Agency Website" | Simon Wiesenthal Center". Wiesenthal.com. 2013-11-06. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "EU drops its 'working definition' of anti-Semitism". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ^ "French concern about race attacks", BBC News, October 2004.

- ^ "France: International Religious Freedom Report 2005", U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Rufin, Jean-Christophe. "Chantier sur la lutte contre le racisme et l'antisémitisme" Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Machine, presented to the French Ministry of the Interior, October 19, 2004.

- ^ Bryant, Elizabeth. "France stung by new report on anti-Semitism," United Press International, October 20, 2004.

- ^ "UK Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks: "The New Anti-Semitism is a Virus"".

- ^ "Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Anti-Semitism" Archived 2013-08-22 at the Wayback Machine, September 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Temko, Ned. "Critics of Israel 'fuelling hatred of British Jews'", The Observer, February 3, 2006.

- ^ MPs deliver anti-Semitism report, BBC News, September 6, 2006.

- ^ "Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Anti-Semitism" Archived 2013-08-22 at the Wayback Machine, September 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Announcement by the Forum, November 18, 2001.

- ^ Summers, Lawrence H. Address at morning prayers Archived 2004-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, September 17, 2002. On the site of Harvard University, accessed January 9, 2006.

- ^ Matas, David. Anti-Zionism and Anti-Semitism. Dundurn Press, Toronto, 2005, pp. 129–144.

- ^ House Passes Chabot’s Bipartisan United Nations Reform Amendment, June 17, 2005. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- ^ Bayefsky, Anne. One Small Step, Wall Street Journal opinion article, June 21, 2004, accessed January 9, 2006.

- ^ Rickman, Gregg J. (2008). "Contemporary global anti-semitism" (PDF). USDOS. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ "ISGAP". isgap.org.

- ^ "Yale Creates Center to Study Antisemitism", Associated Press, September 19, 2006; also see Kaplan, Edward H. & Small, Charles A. "Anti-Israel sentiment predicts anti-Semitism in Europe," Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol 50, No. 4, 548–561, August 2006.

- ^ "The Academic and Public Debate Over the Meaning of the 'New Antisemitism'".

- ^ U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Campus Anti-Semitism (2006) at 72.

- ^ Id.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strauss, Mark (November 12, 2003). "Antiglobalism's Jewish Problem". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on March 12, 2013.

- ^ Oded Grajew, "Debating Anti-Semitism" [letter], Foreign Policy, 1 March 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Maude Barlow, "Debating Anti-Semitism" [letter], Foreign Policy, 1 March 2004, p. 4.

- ^ John Cavanagh, "Debating Anti-Semitism" [letter], Foreign Policy, 1 March 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Mark Strauss, "Debating Anti-Semitism" [letter], Foreign Policy, 1 March 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Walter Laqueur (2006): The Changing Face of Anti-Semitism: From Ancient Times to the Present Day. Oxford University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-19-530429-2 p.186

- ^ Summers, Lawrence. "Address at morning prayers" Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine, Office of the President, Harvard University, September 17, 2002.

- ^ Bergmann, Werner & Wetzel, Juliane. ["Manifestations of anti-Semitism in the European Union" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-04-15. (751 KiB), Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universitaet Berlin, March 2003.

- ^ a b "Global Anti-Semitism Report", U.S. Department of State, January 5, 2005.

- ^ a b Gerstenfeld, Manfred. "Something is Rotten in the State of Europe": Anti-Semitism as a Civilizational Pathology. An Interview with Robert Wistrich" Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine, Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism, Institute for Global Jewish Affairs at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, October 1, 2004.

- ^ a b "France" Archived 2012-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Antisemitism and Racism, Tel Aviv University, 2003.

- ^ Joffe, Josef. "Nations we love to hate: Israel, America and the New Anti-Semitism" Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine, Posen Papers in Contemporary Antisemitism, No.1, Vidal Sassoon Center for the Study of Antisemitism, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004, p.9.

- ^ Joffe, Josef. "Nations we love to hate: Israel, America and the New Anti-Semitism" Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine, Posen Papers in Contemporary Antisemitism, No.1, Vidal Sassoon Center for the Study of Antisemitism, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004, p.12.

- ^ Clark, David. "Accusations of anti-semitic chic are poisonous intellectual thuggery", The Guardian, March 6, 2006.

- ^ a b c Lasn, Kalle. "Why Won't Anyone Say They are Jewish?" Archived 2009-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Adbusters Magazine, March/April 2004

- ^ Raynes-Goldie, Kate. "Race Baiting: Adbusters' listing of Jewish neo-cons the latest wacko twist in left mag's remake" Archived 2007-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Nowtoronto.com, March 18, 2004 – March 24, 2004.

- ^ a b Raynes-Goldie, Kate, "Race baiting Archived 2007-10-18 at the Wayback Machine", Now Magazine, March 18024, 2004

- ^ a b c d e Monnot, Caroline & Ternisien, Xavier. Caroline Monnot and Xavier Ternisien. "Tariq Ramadan accusé d'antisémitisme" Archived 2008-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, Le Monde, October 10, 2003.

- ^ a b Klein, Naomi (April 26, 2002). "Sharon's Best Weapon: The left must confront anti-Semitism head-on". In These Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006.

- ^ "Judeophobia", New Internationalist, October 2004.

- ^ Ma'anit, Adam (October 2004). "A human balance". New Internationalist. No. 372. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015.

- ^ Agbarieh, Asma (October 2004). "Spreading the Stain". New Internationalist. No. 372.

References

- Asserson, Trevor & Williams, Cassie. "The BBC and the Middle East", BBC Watch, retrieved August 20, 2006.

- Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy, University of California Press, 2003; this edition 2006

- Bauer, Yehuda. "Problems of Contemporary Anti-Semitism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2003. Retrieved January 11, 2008., lecture to the Jewish Studies Dept of the University of California, Santa Cruz, 2003, retrieved April 22, 2006.

- Baxter, Sarah. "Wimmin at War"[dead link], The Sunday Times, August 13, 2006, retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Bayefsky, Anne. One Small Step, Wall Street Journal, June 21, 2004, retrieved January 9, 2006.

- Beaumont, Peter. "The new anti-semitism?", '"The Observer, February 17, 2002, retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Berlet, Chip. "ZOG Ate My Brains", New Internationalist, October 2004.

- Berlet, Chip. "Right woos Left", Publiceye.org, December 20, 1990; revised February 22, 1994, revised again 1999.

- Booth, Jenny. "Oona King reveals 'yid' taunts during election", The Times, May 11, 2005.

- Brownfeld, Allan (1987). "Anti-Semitism: Its Changing Meaning". Journal of Palestine Studies. 16 (3). Institute for Palestine Studies: 53–67. doi:10.2307/2536789. ISSN 1533-8614. JSTOR 2536789.

- Bryant, Elizabeth. "France stung by new report on anti-Semitism," United Press International, October 20, 2004.

- Chanes, Jerome. "Review Essay: What's "New" – and what's not – about the New Antisemitism?" Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Political Studies Review 16:1–2 (Spring 2004).

- Chesler, Phyllis The New Anti-Semitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It, Jossey-Bass, 2003. ISBN 0-7879-7803-5

- Conger, George. "UK MPs find leap in anti-Semitism"[permanent dead link], The Jerusalem Post, September 5, 2006.

- Curtis, Polly. "Jewish NUS officials resign over anti-semitism row", The Guardian, April 12, 2005.

- Dershowitz, Alan. The Case For Israel, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, paperback 2004. ISBN 0-471-67952-6

- Doward, Jamie. Jews predict record level of hate attacks", The Guardian, August 8, 2004.

- Dickter, Adam. Fear over European kosher bans, World Jewish Review, July 2002.

- Endelman, Todd M. "Antisemitism in Western Europe Today" in Contemporary Antisemitism: Canada and the World. University of Toronto Press, 2005.

- Finkelstein, Norman. Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

- Fischel, Jack. "The New Anti-Semitism", The Virginia Quarterly Review, Summer 2005, pp. 225–234.

- Fischel, Jack. Antisemitism resurfaces, Midstream, February 1, 2004.

- Fischel, Jack. "Conspiracy Theories as Comfort Food", The Forward, March 29, 2002.

- Forster, Arnold & Epstein, Benjamin, The New Anti-Semitism. McGraw-Hill 1974. ISBN 0-07-021615-0

- Foxman, Abraham H. Never Again? The Threat of the New Anti-Semitism. New York: HarperSanFrancisco (an imprint of HarperCollins), 2003. ISBN 0-06-054246-2 (10); ISBN 978-0-06-054246-7 (13).

- Goodman, Amy. "Finkelstein on DN! No New Antisemitism", interview with Norman Finkelstein, August 29, 2006.

- Harrison, Bernard. The Resurgence of Anti-Semitism: Jews, Israel, and Liberal Opinion. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. 0742552276

- HaLevi, Ezra. "David Duke in Syria: Zionists Occupy Washington, NY and London", Arutz Sheva, November 29, 2005; see clip of David Duke's interview in Syria.

- Halkin, Hillel. "The Return of Anti-Semitism," Commentary, February 2002

- Hodgson, Jessica. "Editor apologises for 'Kosher Conspiracy' furore", The Guardian, February 7, 2002.

- Ioanid, Radu. Foreword in Taguieff, Pierre André. Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe. Ivan R. Dee, 2004.

- Jaffe, Ben-Zion. "Big Jew on Campus: The Jewish obsession", Jerusalem Post Blog Central, December 11, 2005.

- Kaplan, Edward H. & Small, Charles A. "Anti-Israel sentiment predicts anti-Semitism in Europe," Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol 50, No. 4, 548–561, August 2006.

- Kinsella, Warren. The New anti-Semitism, retrieved March 5, 2006.

- Klug, Brian. The Myth of the New Anti-Semitism Archived 2009-07-01 at the Portuguese Web Archive. The Nation, posted January 15, 2004; February 2, 2004 issue.

- Klug, Brian. Israeli, Antisemitism and the left, Red Pepper, November 24, 2005.

- Klug, Brian. "In search of clarity", Catalyst, March 17, 2006.

- Landes, Richard. "Michael Lerner Weighs in, Disturbingly", Augean Stables, February 5, 2007.

- Lazare, Daniel. "The Chosen People", The Nation, December 19, 2005.

- Lerman, Tony. "Reflecting the reality of Jewish diversity", The Guardian: Comment is Free, February 6, 2007, retrieved August 11, 2007.

- Lerner, Michael. There Is No New Anti-Semitism, posted February 5, 2007, retrieved February 6, 2007.

- Lewis, Bernard. "The New Anti-Semitism", The American Scholar, Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on March 24, 2004.

- Liddle, Rod. "Just how many islands does Spain want?", The Guardian, July 17, 2002.

- Lipstadt, Deborah. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. Penguin 1994.

- Kenneth L. Marcus, Jurisprudence of the New Anti-Semitism, Wake Forest Law Review, Vol. 44, 2009. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1376592

- Matas, David. Anti-Zionism and Anti-Semitism. Dundurn Press, Toronto, 2005. ISBN 1-55002-553-8

- Prager, Dennis & Telushkin, Joseph. Why the Jews? The Reasons for Antisemitism. Simon & Schuster, 2003.